Pilgriming, within and without

Pilgrimage and psychedelic work through the Hero’s Journey’s lens.

<TL;DR: Framework of pilgrimage as an embodied Hero’s Journey and psychedelic work as an inner one—may help us navigate those spaces.>

In nine days, I embark on a pilgrimage of sorts—to the depths of the Brazilian Amazon to sit in dieta (pronounced dyeh-tah) with the Ashaninka tribe: an intense 10-day process where Ayahuasca is likely had every single night, all night. With that, pilgrimage is on my mind.

This won’t be my first or longest departure from 3D life. In 2024, I sat six weeks in complete silence. Prior to that, I took part in numerous vision quests, Vipassana, and other retreats, and have had—and witnessed—many psychedelic journeys, which I believe to be a version of modern pilgrimage.

Below I offer a way to navigate both traditional pilgrimage and psychedelic work as forms of Hero’s Journey.

About Pilgrimage

Modern Western life is largely devoid of pilgrimage, yet pilgrimage is central to nearly every spiritual lineage, faith, and culture around the world. From ancient rituals to contemporary practices, the concept of pilgrimage persists across time and geography.

Universality of Pilgrimage

In Judaism, pilgrimage to Jerusalem during Passover, Shavuot, and Sukkot was once commanded in Torah. Entire communities traveled to the Temple, anchoring faith in movement and shared ritual.

Christian pilgrims have long walked to Jerusalem, Rome, and later Santiago de Compostela, seeking healing, penance, and grace. By the 4th century, pilgrimage had become a practice of spiritual renewal and connection to sacred history.

In Islam, pilgrimage is foundational. The Hajj to Mecca—one of the five pillars—draws millions who retrace the footsteps of Abraham, Hagar, and Ishmael. The journey reenacts the search for water, the sacrifice that wasn’t, and the circling of the Kaaba. It affirms surrender, remembrance, and unity.

Hinduism places pilgrimage (yatra) at its core. Millions journey to sacred rivers, temples, and mountains—from Char Dham to the vast gatherings of Kumbh Mela—for purification and divine encounter.

Buddhists walk to the four sites of the Buddha’s life—Lumbini, Bodh Gaya, Sarnath, and Kushinagar. Tibetan Buddhists, with full-body prostrations, travel to places like Mount Kailash. The journey itself becomes a form of meditation and devotion.

In Japan, Shinto pilgrims walk ancient trails like the Kumano Kodo and visit shrines such as Ise Jingū. The path honors the kami—spiritual forces woven into the land—and affirms harmony with nature.

Sikhs journey to the Golden Temple in Amritsar, centering on prayer, selfless service, and presence with the Guru. Though smaller in global number, the depth of devotion is profound.

Indigenous traditions also carry deep pilgrimage lineages. In Mesoamerica, pilgrims traveled to sites like Teotihuacan to reenact cosmic myths and seek harmony with the divine. In the Andes and beyond, journeys into the mountains offer healing and vision. Across the African continent, pilgrims return to ancestral lands and sacred sites to commune with spirits and honor the dead. Aboriginal Australians walk the songlines—spiritual tracks left by ancestral beings—embodying memory, movement, and land as one.

Many other branches and communities—Sufis, Hasidic Jews, Jain monks, Christian mystics, Daoist seekers—also take up the path, each adding to the long, winding tradition of pilgrimage.

Intro to the Hero’s Journey

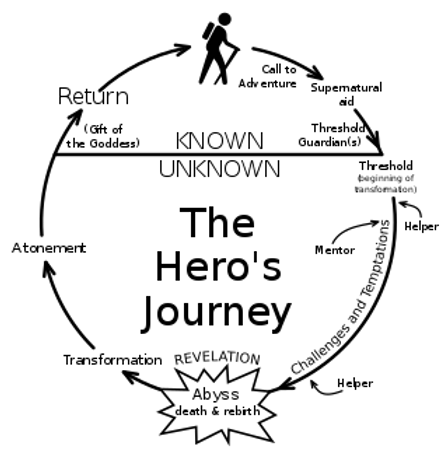

The Hero’s Journey is a monomyth introduced by Joseph Campbell that outlines the elements of every hero’s path.

Here’s an illustration of it:

In another life, I wrote and produced a TED talk about The Hero’s Journey—for which I pulled the steps of three very different journeys: The Lion King, Titanic, and Fight Club, demonstrating how they all follow the same 12 steps. You can watch it here: TEDx Talk

Pilgrimage as an Embodied Hero’s Journey

I find that elements of pilgrimage correspond quite neatly with the Hero’s Journey:

The Call to Adventure: A pilgrimage is a departure from one’s home and daily life—an adventure.

Meeting a Mentor: The pilgrim learns about the pilgrimage from those who took the journey before, from scripture, or by revelation. Pilgrimages often follow celestial calendars, harvest seasons, or spiritual cycles adhering to an order greater than self.

Crossing the Threshold: One leaves their home. Unlike metaphorical quests, pilgrimage requires physical movement—whether walking, limping, or being wheeled in.

Helpers: Pilgrims must plan for their journey—water, nourishment, accommodation. They may help themselves or rely on resources along the way.

Trials and Temptations: By design or circumstance, the pilgrimage strips away some comforts and asks for some abstinence. Sex and alcohol may be forbidden, sleep thins, food may be altered. There is sacrifice in the sacred.

Initiation: Often marked by arrival at the destination, the finding of the medicine, or the receiving of guidance.

The Return with the Elixir: All pilgrimages end—with the return of the pilgrim to their home. Often, if not always, changed.

Modern-Day Alternatives to traditional pilgrimage

Many pilgriming cultures have lost their pilgrimage paths or faded away altogether. In the absence of pilgrimage, modern-day alternatives have emerged to fill the void—wilderness retreats, long-distance hikes like the Camino de Santiago, immersive rites-of-passage programs, silent meditations including Vipassana and Zen, Burning Man and other outdoor festivals, music tours, vision quests, and psychedelic medicine work are but a few examples.

Psychedelic Work as an Inner Hero’s Journey

Having witnessed thousands of successful psychedelic journeys—and learned of many more—I find that psychedelic work, done right, corresponds quite neatly with the Hero’s Journey, albeit not always in a neat chronological order. (Perhaps Terence McKenna, a pioneer of the psychedelic movement, was already alluding to this analogy when he named a 5-gram dose of mushrooms a ‘heroic dose.’)

The Call to Adventure: An altered-state journey is a departure from normal life. One often speaks of a calling toward it—internal or external.

Meeting a Mentor: The person follows a teacher, a medicine, or a practice, surrendering to a knowing or a being greater than themselves.

Crossing the Threshold: The medicine is consumed and comes on. Consciousness is altered. One is… tripping. They have entered the unknown.

Trials and Temptations: In a psychedelic journey, the Default Mode Network becomes undone. I liken it to closing the main streets of a city—those often prone to traffic. While the closed streets are being worked on, those traveling around town are forced to take alternative pathways, marked by heightened activity in other areas.

This may feel uncomfortable—the first step of a house cleaning may involve noticing how messy it got.

Helpers: Helpers may be those holding space for the altered-state experience. Help may be just as well be found in a piece of music or a ray of light, a plant, a memory, or a sense of inner guidance or formless support.

Revelation / Transformation: In the absence of the Default Mode Network, other areas of the brain come online. This may be experienced as an aha moment, a letting go, compassion toward self and others, a regained sense of vitality or creativity, a retrieval of a younger part, or a quiet knowing that one is safe, worthy, lovable. This may be ecstatic, subtle, or cathartic. The hero is changed.

The Return with the Elixir: Grounding and integration are as important as can be. Herein begins the real work: how does one apply themselves IRL, in a way that is informed by what they have shed, transmuted, gained, or learned?

Here’s hoping the framework above helps travelers better orient throughout their journeys, find solace in the less comfortable parts, and better integrate the elixir they return with—perhaps in service to something greater than themselves.

Safe travels—in 3D and all Ds.